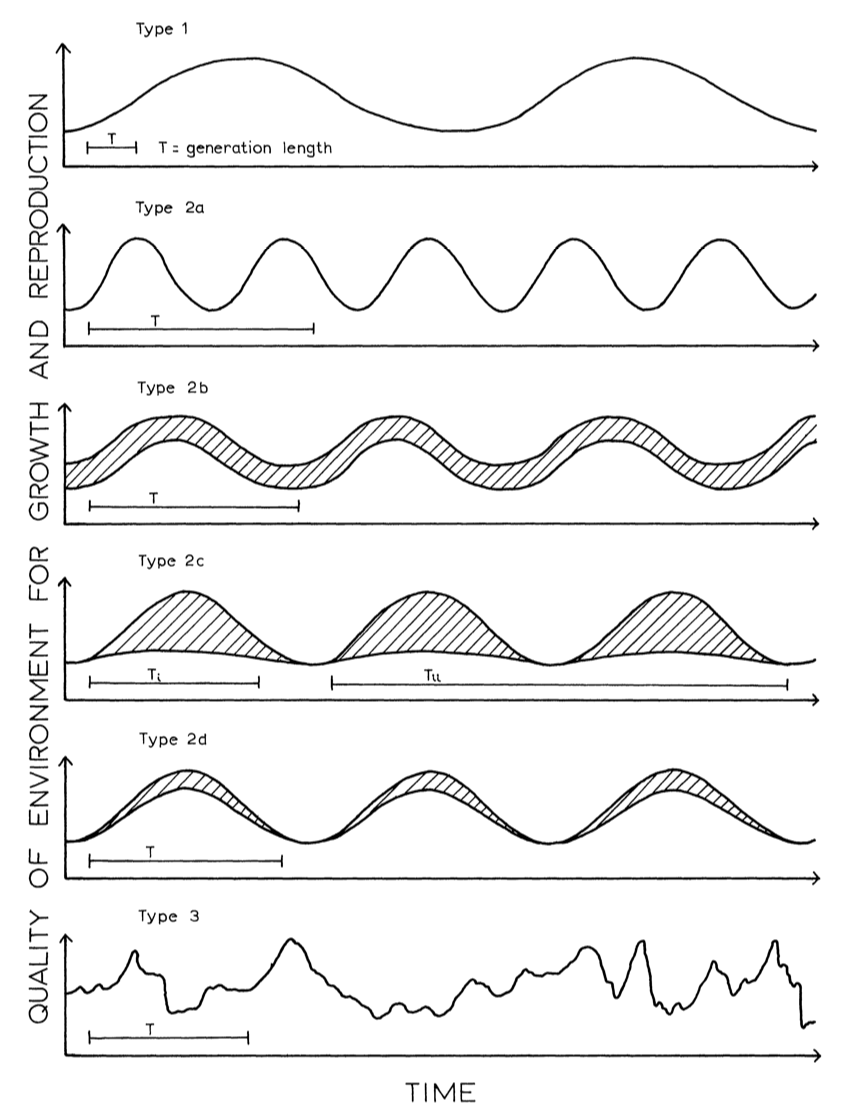

Park yourself on a beach towel at the coast for long enough, and you will likely experience a fraction of the environmental stress intertidal animals see on a regular basis. But they thrive in this environment, partially due to their physiological plasticity. Plasticity is a trait commonly seen in organisms that experience a high degree of environmental fluctuations within their lifetimes, making plastic species more suited to experience a wide range of conditions and partition their energy appropriately. But what happens when the frequency of the fluctuation is much wider, on the seasonal or yearly timescale? For species that have generation times that align with fluctuations on this scale, transgenerational plasticity is potentially adaptive. This concept is explained very well by a figure in Stearns (1976), where the generation time matches predictable fluctuations in environmental condition, but not in an adaptive way under unpredictable fluctuations in environmental condition.

Figure 1. Adapted from Stearns 1976, where generation time depends on predictability and duration of fluctuations in environmental condition.

While on the surface it appears that our field disagrees on what transgenerational plasticity entails, it is more accurate to say that we disagree on how to disentangle the effects of transgenerational, developmental, and adult plasticity in our experimental designs. Put simply, transgenerational plasticity is defined as the non-genetic effects observed in offspring due to environmental exposure of the previous generations. We would expect transgenerational plasticity to be non-adaptive under climate change scenarios, as climate change will increase the unpredictability of environmental fluctuations. Co-authors and I set out to investigate this question in a direct developing sea hare, taking advantage of life history characteristics that reduce gene flow to understand the role of transgenerational plasticity in a species living in predictably fluctuating estuaries.

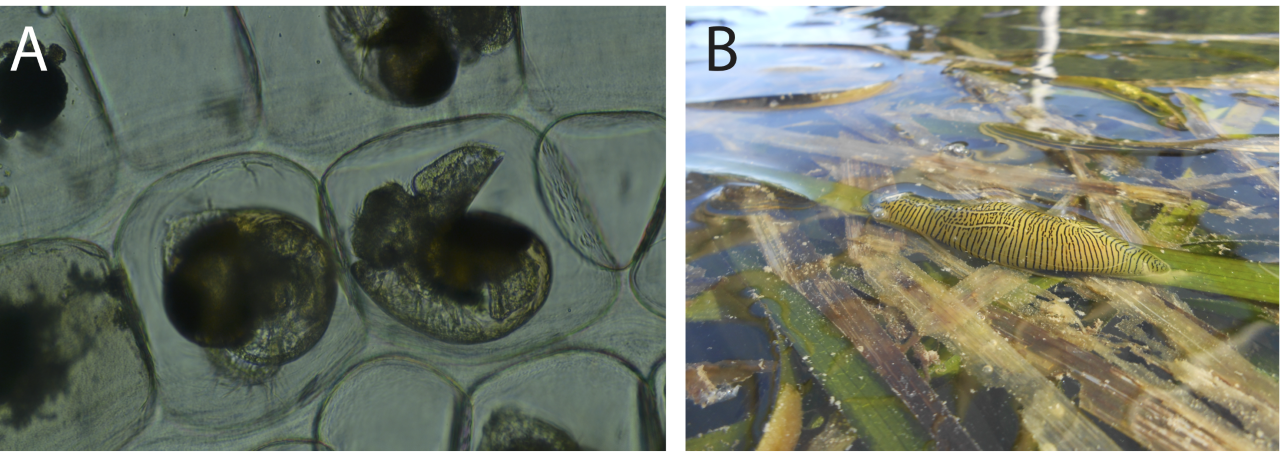

The eelgrass sea hare, Phyllaplysia taylori, has two non-overlapping generations in Central California and lives in intertidal eelgrass beds that are predictably fluctuating in temperature, among other conditions. Sea hare adults living in the spring give rise of sea hare adults living in the summer/early fall, which are characterized by two very different thermal regimes: high fluctuations and low mean temperature in the spring, and low fluctuations and high mean temperature in the fall. In conducting another study on adult reversible plasticity in this same species, we noticed that season was a major player in the physiological response to increased temperature: spring adults had a high capacity for acclimation (high plasticity) but lower tolerance and summer adults had a low capacity for acclimation but higher tolerance overall. This result harkened back to the Trade-Off Hypothesis, a prevalent topic in the Stillman Lab regarding an energy allocation trade-off between thermal tolerance plasticity and absolute thermal tolerance. The question arose: is this seasonally-based adult phenotype driven by transgenerational plasticity? And further, will it persist with climate change?

Figure 2. A) Sea hare embryos and B) Adult eelgrass sea hare.

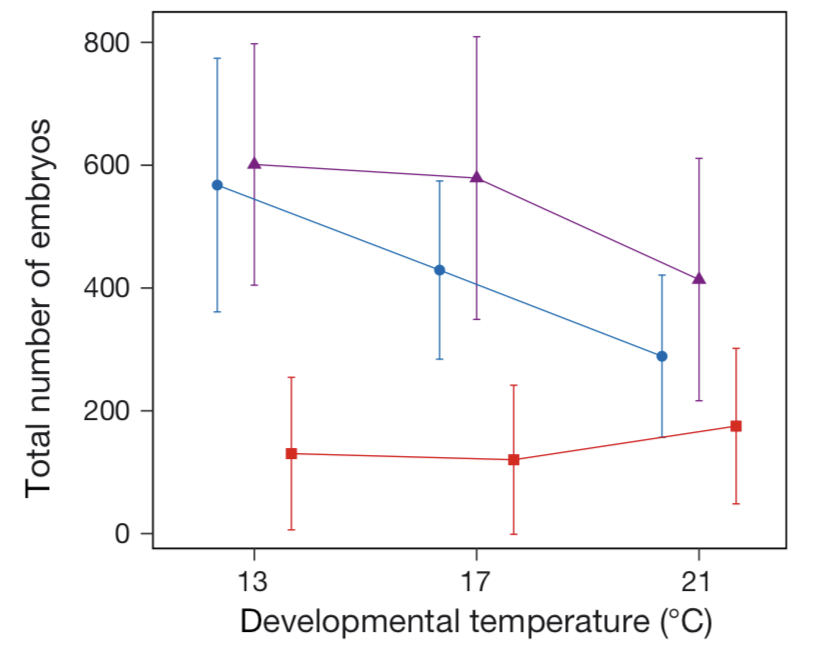

Acclimating sea hares to conditions representative of spring and summer conditions, alongside a “future summer” condition, and fully crossing offspring back to these conditions, we found that a combination of transgenerational plasticity and developmental plasticity accounts for the seasonal phenotype shift. However, future conditions – whether represented by that “future summer” condition or acute heat shock during early development (simulating an extreme heat event), result in incomplete compensation by maternal provisioning and decreased offspring success. In simple terms, this means that transgenerational plasticity in sea hares successfully maintains seasonal phenotypes in the current, predictable thermal regime, but future conditions disrupt this relationship and could lead to population declines.

Figure 3. Significantly fewer successful offspring under any future conditions (in red, also points in right-most position). Figure adapted from Tanner et al. 2020 MEPS.

In the context of the greater field, sea hare transgenerational plasticity falls squarely in the middle of the pack when it comes to positive or negative effects under climate change. And this is no surprise, since we expect transgenerational plasticity to only be advantageous under predictable regimes (and not all study systems where it is investigated have that characteristic). Many recent review articles have called for more standardization of studies investigating transgenerational effects, and we still have a long way to go in parsing these effects at the species level, let alone at the community-ecosystem level. However, it is an extremely intriguing avenue of research for those of us interested in rapid adaptation to climate change – it could be a major player in non-genetic, physiological-based acclimatization on a short timescale that buffers the effects of climate change.

Biography

Dr. Richelle Tanner is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at Washington State University, specializing in marine evolutionary and environmental physiology, climate change effects, and bioinformatics. She also serves as chair of the Science Partnerships Committee of the National Network for Ocean and Climate Change Interpretation.

Relevant Literature

Donelson, J. M., Salinas, S., Munday, P. L. & Shama, L. N. S. Transgenerational plasticity and climate change experiments: Where do we go from here? Global Change Biology 24, 13–34 (2018).

Eirin-Lopez, J. M. & Putnam, H. M. Marine environmental epigenetics. Annual Review of Marine Science 11, 335-368 (2019).

Galloway, L. F. & Etterson, J. R. Transgenerational plasticity is adaptive in the wild. Science 318, 1134–1136 (2007).

Leimar, O. & McNamara, J. M. The evolution of transgenerational integration of information in heterogeneous environments. The American Naturalist 185, E55–E69 (2015).

Ross, P. M., Parker, L. & Byrne, M. Transgenerational responses of molluscs and echinoderms to changing ocean conditions. ICES Journal of Marine Science: Journal du Conseil fsv254 (2016).

Stearns, S. C. Life-History Tactics: A Review of the Ideas. The Quarterly Review of Biology 51, 3–47 (1976).

Tanner, R. L., Bowie, R. C. K. & Stillman, J. H. Parental effects on thermal tolerance plasticity under climate change scenarios in the eelgrass sea hare. Marine Ecology Progress Series 634, 199–211 (2020).