Under global change conditions such as varying temperature, light and turbidity, many corals have experienced a breakdown of their relationship with their endosymbionts. Fracturing of this obligate symbiosis can lead to bleaching and ultimately mortality (Heron et al. 2013). At the edges of their physiological limits, corals may be more vulnerable to mortality because they expend more energy to survive (Portner 2012); they may generate more mucus in order to clear sediment, burn storage compounds to thermoregulate, or increase photosynthetic machinery to take advantage of high light conditions. But exactly how much energy is needed to survive (& thrive) in a rapidly changing ocean?

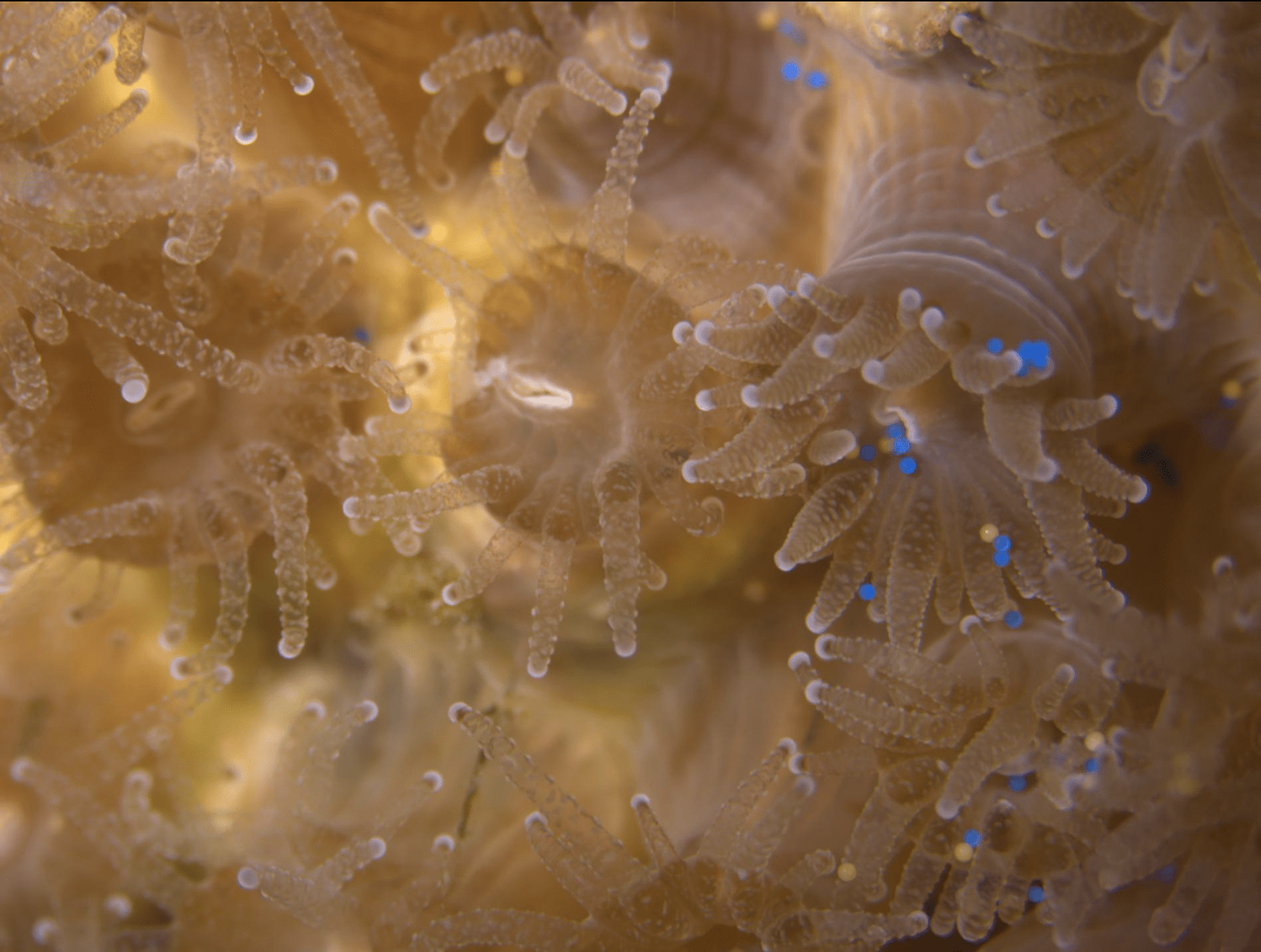

All organisms have a finite amount of energy to allocate to all functions necessary for life: homeostasis, maintenance, growth, and reproduction to name a few. Animals that many of us are familiar with attain energy via predation (heterotrophy) of other living things. Plants, however, have the unique ability of creating their own food from sunlight via photosynthesis. Corals are a particularly interesting case, because the coral animal has plant algal cells within its cells (endosymbionts). Although corals still engage in heterotrophy via their stinging nematocyst cells, the symbiont cells generate photosynthates that are transferred to the host (Muller et al. 2009). In an era of global change, what are the dynamics of this coral-algal symbiotic relationship? Will corals have the energy they need to adapt?

A dynamic energy budget (DEB) is a computationally and mathematically complex model, coded in MATLAB, that explains the energetic input, processing, and output of an organism from birth to death. First explained by Bas Kooijman, it applies mathematical, chemical, and biological theory & data to explain the flow of energy through organisms, from a bacterium to an elephant (Kooijman 2010). Our research asserts that modelling a coral’s dynamic energy budget (DEB) can provide insight into whether corals have the necessary resources to develop, reproduce, and maintain homeostasis in challenging environments (Augustine et al. 2014).

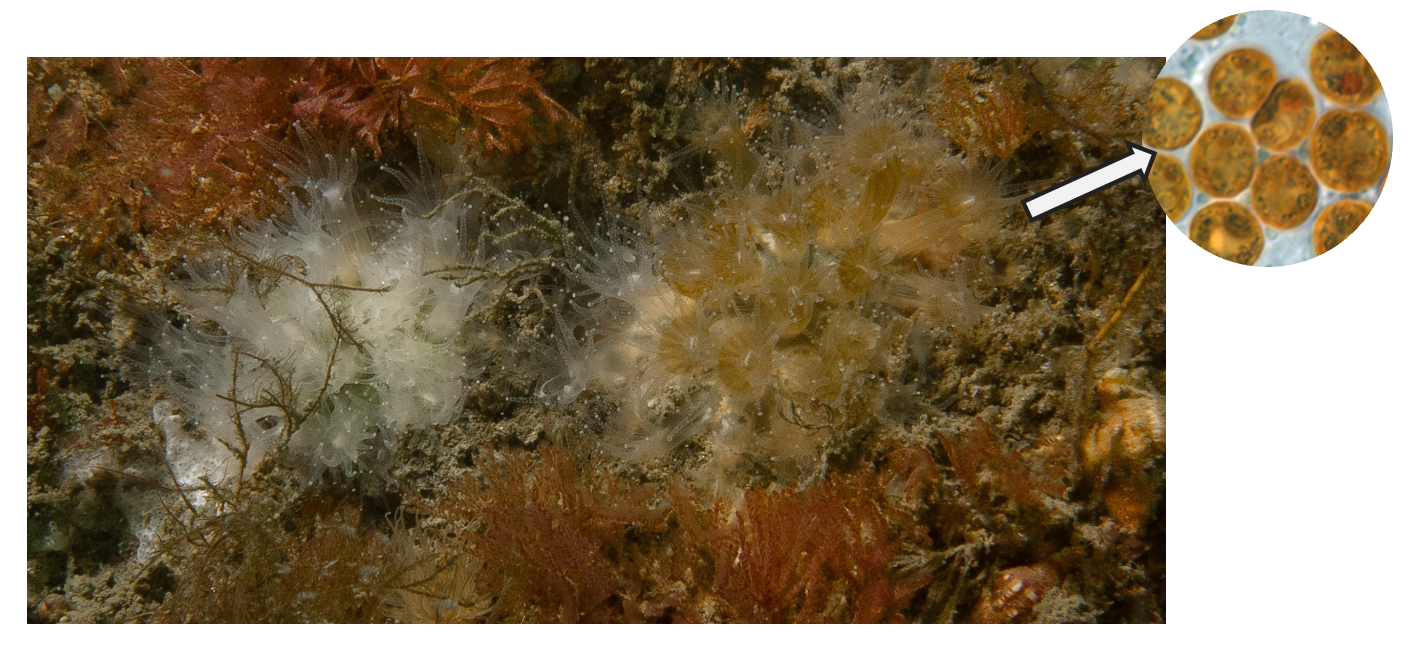

The temperate scleractinian coral Astrangia poculata occurs across the Atlantic US from Florida to southern Massachusetts (Saba et al. 2015). A. poculata provides a unique opportunity to investigate the energetic costs and benefits of coral-algal associations because it is facultatively symbiotic, occurring on a spectrum of symbiont densities: from symbiotic colonies, richly brown in color and high in symbiont density, and aposymbiotic–bleached in color and lacking symbionts (Dimond et al. 2008). In tropical corals, we know that symbionts confer a large advantage to corals (Muller et al. 2009, Cunning et al. 2017, van Oppen et al. 2015, Clarr et al. 2020), and corals are reliant on the transfer of photosynthates to stay alive. Therefore, we may be tempted to believe that symbionts confer such an advantage to temperate Astrangia corals living in harsh conditions: wouldn’t they want to maintain high symbiotic densities and scarf up all the photosynthates they possibly could? However, we also know from previous research that temperate Astrangia corals attain the majority of their energy from heterotrophy, regardless of symbiont status (Dimond et al. 2007). This leads us to our overarching, fundamental question: are there energetic or evolutionary advantages (i.e. faster growth, survivability, or fecundity) for facultatively symbiotic A. poculata to possess symbionts? Do these advantages make certain corals more resilient to global change (increased temperature, acidity, pollution)?

There has been lots of empirical work on Astrangia as a facultative system, teasing apart the roles of host and symbiont (Dimond et al. 2013, Sharp et al. 2017, Burmester et al. 2018, DeFilippo et al. 2017, Aichelman et al. 2019, Wuitchik et al. 2021, DiRoberts et al. 2021). However, a complete dynamic energy budget (DEB) model for any facultative symbiosis system comparing symbiotic states has not yet been attempted. In collaboration with Erik Muller, Roger Nisbet, Randi Rotjan, and Justin McAlister, I am currently developing a new DEB model to examine energy flux in symbiotic and aposymbiotic A. poculata corals, based on theory and modeling code from tropical corals (Muller et al. 2009). This tropical model asserts that symbionts only transfer photosynthates that are in surplus, and the host delivers its excess nutrients, in the form of nitrogen. However, this model needs to be fundamentally changed to accommodate a range of symbiotic states and more extreme temperate environmental conditions. Drawing upon 10 years of physiological A. poculata research completed by the Rotjan lab (Burmester et al. 2018, Rotjan et al. 2019, DeFillipo et al. 2017), and adding remaining empirical measurements to inform the model, our collaborative team will comprehensively complete energy calculations and determine the effect of environmental conditions (if any) on the symbiotic status of A. poculata corals.

Because we know that Astrangia gets most of its energy from heterotrophy, rather than transferred photosynthates (regardless of sym status, Dimond et al. 2007), they may be vulnerable to environmental pollutants that compromise their energy budget; they must expend more energy to maintain homeostasis when filtering/ridding themselves of toxins. Interestingly, Astrangia exist in and around urban harbors of cities along the east coast of the United States, including major metropolitan areas such as New York City and Miami, Florida. Here, they are exposed to urban toxicants such as phthalates, lead, microplastics, caffeine, and pharmaceuticals from coastal runoff & wastewater effluent (Heery et al. 2018). Though the impact of urban pollutants on marine organisms is well studied (Heery et al., 2018 and references therein), it is unclear if these impacts will be amplified by the impacts of global change, specifically, temperature. Interacting impacts of increased temperature with urban ecotoxicological exposure may challenge the apparent resiliency of marine organisms beyond each stressor on its own. In addition, while we have some idea of how adult corals respond to ecotoxicity, very little is known how urban pollutants affect coral early life history stages, i.e. eggs and larvae. Eggs and larvae are exposed to the exact same ecotoxicological conditions as the adults, but are smaller in size and larger in surface area to volume ratio, so their developing cells may be more vulnerable to urban stressors.

Our lab focuses on two ubiquitous and persistent urban pollutants: microplastics and caffeine, which are only partially filtered by wastewater treatment plants (Raju et al. 2019 & Peeler et al. 2006). Previous work from Rotjan et al. 2019 has shown that adult Astrangia do, in fact, ingest a lot of microplastics– over 100 microplastics per polyp! The corals actually preferentially take up the microplastics over their own food, which calls into question larger energetic physiological questions (Rotjan et al. 2019). Namely, does Astrangia have enough energy to survive urban stressors, especially under high temperature global change conditions? Will photosynthates transferred by symbionts buffer the energetic impacts of ecotoxicants in Astrangia colonies? In order to probe this question, first we need to understand Astrangia energetics & the dynamics of their symbiosis.

At the intersection of urban environmental challenges and global change, a dynamic energy budget (DEB) model is a useful tool to probe the resilience of marine organisms. All living organisms have a finite amount of energy with which to grow, maintain homeostasis, and reproduce. Investigating the dynamics of energetic tradeoffs in a rapidly changing planet will inform conservation & management decisions in our vulnerable oceans for decades to come.

References:

Aichelman, H. E., R. C. Zimmerman, and D. J. Barshis. 2019. Adaptive signatures in thermal performance of the temperate coral Astrangia poculata. Journal of Experimental Biology 222:.

Augustine, S., S. Rosa, S. A. L. M. Kooijman, F. Carlotti, and J. Poggiale. 2014. Modeling the eco-physiology of the purple mauve stinger, Pelagia noctiluca using Dynamic Energy Budget theory. Journal of Sea Research 94:52-64.

Burmester, E. M., A. Breef‐Pilz, N. F. Lawrence, L. Kaufman, J. R. Finnerty, and R. D. Rotjan. 2018. The impact of autotrophic versus heterotrophic nutritional pathways on colony health and wound recovery in corals. Ecology and Evolution 8:10805-10816.

Claar, D. C., S. Starko, K. L. Tietjen, H. E. Epstein, R. Cunning, K. M. Cobb, A. C. Baker, R. D. Gates, and J. K. Baum. 2020. Dynamic symbioses reveal pathways to coral survival through prolonged heatwaves. Nature Communications 11:6097.

Cunning, R., E. B. Muller, R. D. Gates, and R. M. Nisbet. 2017. A dynamic bioenergetic model for coral-Symbiodinium symbioses and coral bleaching as an alternate stable state. Journal of Theoretical Biology 431:49-62.

DeFilippo, L., E. M. Burmester, L. Kaufman, and R. D. Rotjan. 2016. Patterns of surface lesion recovery in the Northern Star Coral, Astrangia poculata. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 481:15-24.

Dimond, J., and E. Carrington. 2008. Symbiosis regulation in a facultatively symbiotic temperate coral: zooxanthellae division and expulsion. Coral Reefs 27:601-604.

Dimond, J., and E. Carrington. 2007. Temporal variation in the symbiosis and growth of the temperate scleractinian coral Astrangia poculata. Marine Ecology Progress Series (Halstenbek) 348:161-172.

Dimond, J., A. Kerwin, R. Rotjan, K. Sharp, F. Stewart, and D. Thornhill. 2013. A simple temperature-based model predicts the upper latitudinal limit of the temperate coral Astrangia poculata. Coral Reefs 32:401-409.

DiRoberts, L., A. Dudek, N. Ray, R. Fulweiler, and R. Rotjan. 2021. Testing assumptions of nitrogen cycling between a temperate, model coral host and its facultative symbiont: symbiotic contributions to dissolved inorganic nitrogen assimilation.

Heery, E. C., B. W. Hoeksema, N. K. Browne, J. D. Reimer, P. O. Ang, D. Huang, D. A. Friess, L. M. Chou, L. H. L. Loke, P. Saksena-Taylor, N. Alsagoff, T. Yeemin, M. Sutthacheep, S. T. Vo, A. R. Bos, G. S. Gumanao, M. A. Syed Hussein, Z. Waheed, D. J. W. Lane, O. Johan, A. Kunzmann, J. Jompa, Suharsono, D. Taira, A. G. Bauman, and P. A. Todd. 2018. Urban coral reefs: Degradation and resilience of hard coral assemblages in coastal cities of East and Southeast Asia. Marine Pollution Bulletin 135:654-681.

Heron, S. F., J. A. Maynard, R. van Hooidonk, and C. M. Eakin. 2016. Warming Trends and Bleaching Stress of the World’s Coral Reefs 1985–2012. Scientific Reports 6:38402.

Kooijman, S. A. L. M. 2010. Dynamic Energy Budget theory for metabolic organisation.

Muller, E. B., S. A. L. M. Kooijman, P. J. Edmunds, F. J. Doyle, and R. M. Nisbet. 2009. Dynamic energy budgets in syntrophic symbiotic relationships between heterotrophic hosts and photoautotrophic symbionts. Journal of Theoretical Biology 259:44-57.

Pörtner, H. O. 2002. Climate variations and the physiological basis of temperature dependent biogeography: systemic to molecular hierarchy of thermal tolerance in animals. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, Part A 132:739-761.

Raju, S., M. Carbery, A. Kuttykattil, K. Senthirajah, A. Lundmark, Z. Rogers, S. SCB, G. Evans, and T. Palanisami. 2020. Improved methodology to determine the fate and transport of microplastics in a secondary wastewater treatment plant. Water Research (Oxford) 173:115549.

Rotjan, R. D., K. H. Sharp, A. E. Gauthier, R. Yelton, E. M. B. Lopez, J. Carilli, J. C. Kagan, and J. Urban-Rich. 2019. Patterns, dynamics and consequences of microplastic ingestion by the temperate coral, Astrangia poculata. Proceedings of the Royal Society. B, Biological Sciences 286:20190726.

Saba, V. S., S. M. Griffies, W. G. Anderson, M. Winton, M. A. Alexander, T. L. Delworth, J. A. Hare, M. J. Harrison, A. Rosati, G. A. Vecchi, and R. Zhang. 2016. Enhanced warming of the Northwest Atlantic Ocean under climate change. Journal of Geophysical Research. Oceans 121:118-132.

Sharp, K. H., Z. A. Pratte, A. H. Kerwin, R. D. Rotjan, and F. J. Stewart. 2017. Season, but not symbiont state, drives microbiome structure in the temperate coral Astrangia poculata. Microbiome 5:120.

van Oppen, Madeleine J H, J. K. Oliver, H. M. Putnam, and R. D. Gates. 2015. Building coral reef resilience through assisted evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences - PNAS 112:2307-2313.

Wuitchik, D. M., A. Almanzar, B. E. Benson, S. Brennan, J. D. Chavez, M. B. Liesegang, J. L. Reavis, C. L. Reyes, M. K. Schniedewind, I. F. Trumble, and S. W. Davies. 2021. Characterizing environmental stress responses of aposymbiotic Astrangia poculata to divergent thermal challenges. Molecular Ecology 30:5064-5079.

Biography

Caroline Fleming (she/her/hers) is a PhD student and an NSF GRFP Award Winner in the Biology Department & URBAN Biogeoscience and Environmental Health Program at Boston University. An ecophysiologist at heart, Caroline has dipped her toes in population ecology, phylogeography, and epigenetics. When not in the lab or rifling through the nearest tide pool, you can find Caroline putting her Art History minor to work, or hiking to the top of just about any peak she can find.