by Nicola Kriefall (thenicolakriefall@gmail.com)

The third largest barrier reef in the world lives in the Florida Keys, and it’s the only one that the continental United States has. Snorkeling, diving, and fishing across this area generates millions in tourism revenue and supports hundreds of thousands of jobs every year. I grew up visiting the Keys to snorkel, then received my scuba certification there, and now I am frequently returning there to conduct field work as a PhD student.

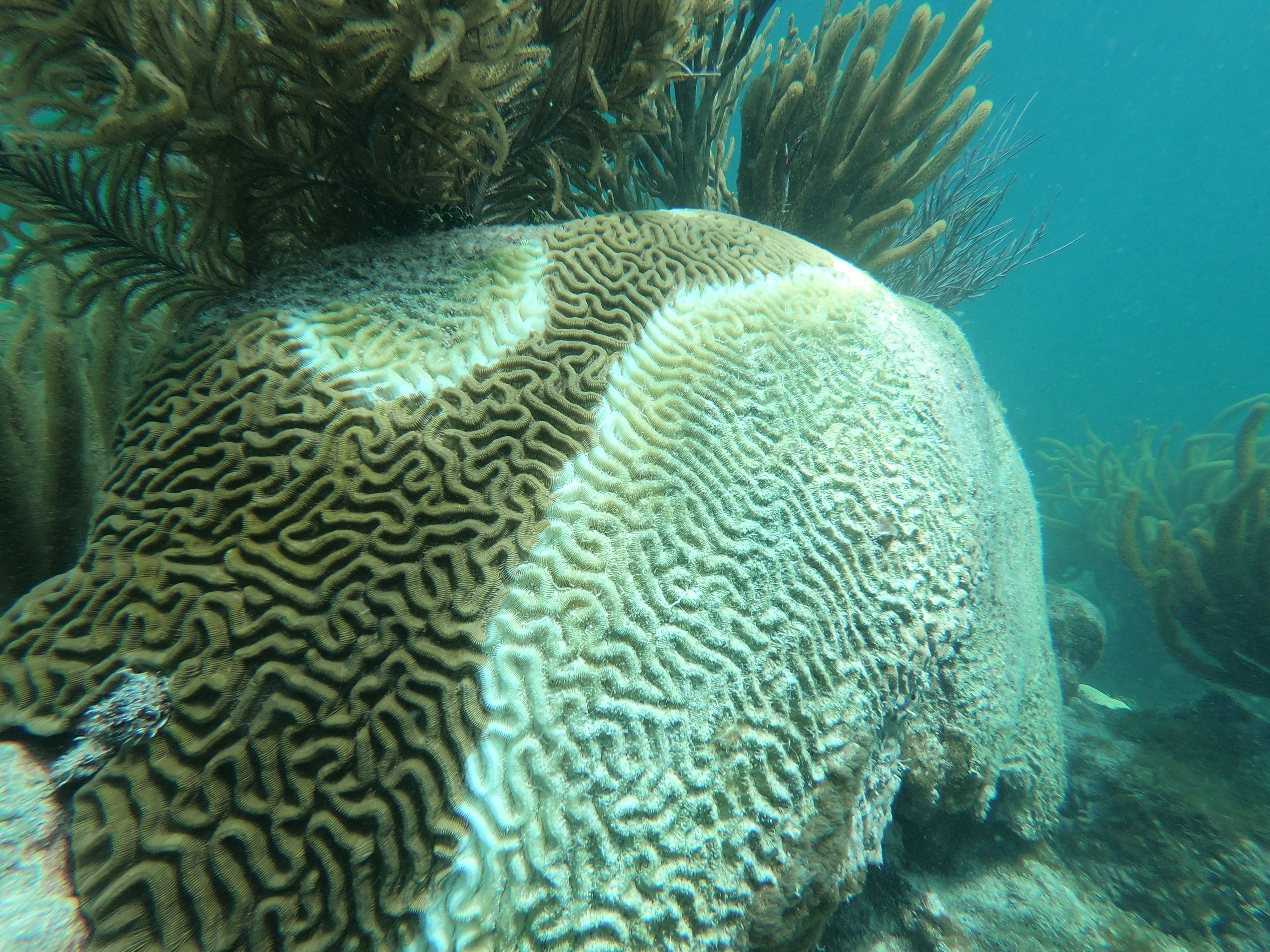

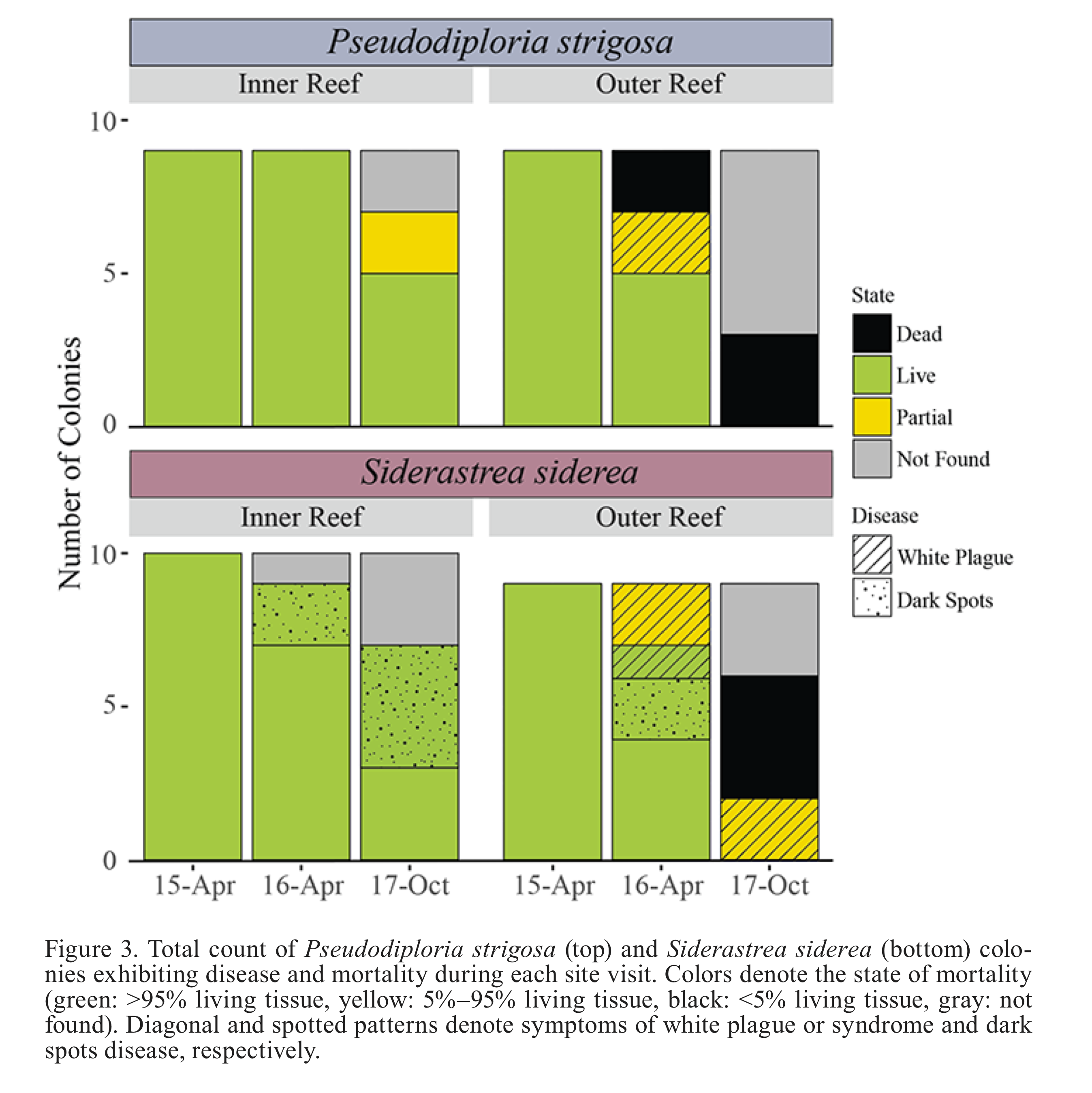

Unfortunately, my field work in the Keys has been rather disheartening. These reefs, and reefs across the world, face an onslaught of challenges, including climate change, pollution, and overfishing, to name a few. The already weakened Florida Keys corals were then hit by category 4 Hurricane Irma in September 2017, which physically damaged them and suspended sediment in the water column to block light for months afterwards. On top of, or perhaps because of, all of these issues, there have also been unprecedented disease outbreaks devastating multiple species of corals (see below for one example, on brain coral Pseudodiploria strigosa).

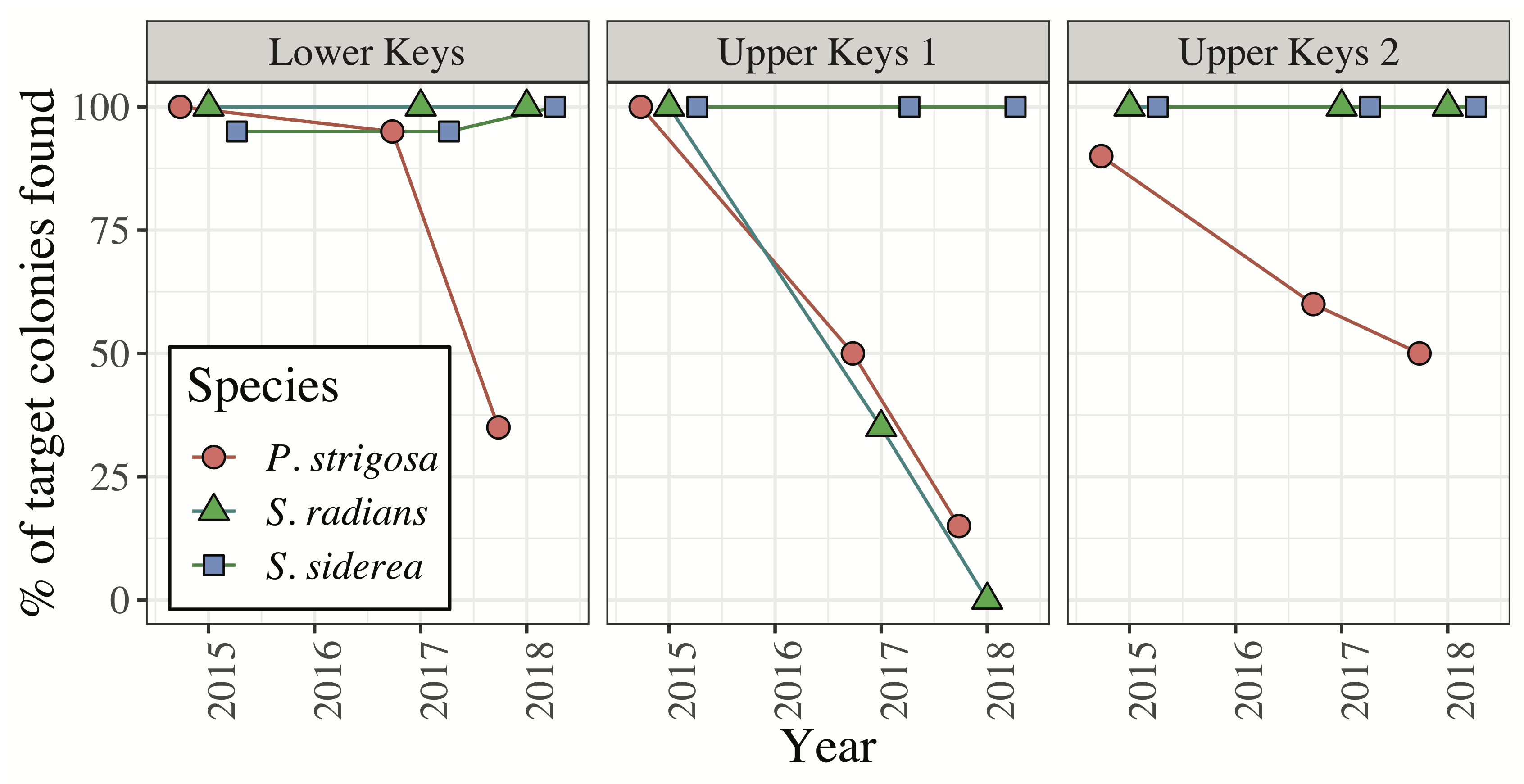

My field work began as a simple growth monitoring project, but for most of my corals, the aforementioned problems were too much to bare. Year after year I returned to my study sites and watched as they slowly succumbed to disease or were just missing from where they should have been, potentially swept away by the hurricane (see below; from Rippe, Kriefall, et al., 2019). Where we usually sampled at least 10 corals easily at a site, we then had trouble finding any of them at some sites.

The three reef-building species of coral that I study are the massive starlet coral Sideratrea siderea, lesser starlet coral Siderastrea radians, and symmetrical brain coral Psuedodiploria strigosa. The symmetrical brain coral is my personal favorite in terms of aesthetics, but sadly is also the most sensitive to the ongoing environmental trials (see below). On the bright side, the massive starlet coral Siderastrea siderea and its congener S. radians appear to be doing relatively well at most sites, compared to most other hard coral species.

Most of our sites have already transitioned from dominant reef-building coral species to vast expanses of soft corals (see below for a photo of a dead Siderastrea siderea colony that was likely over a hundred years old, surrounded by soft corals). For scientists and residents in the area, this has been a devastating loss. Beyond just losing beautiful species, the ecosystem services that soft corals and algal turf provide hardly measure up to the physical protection that stony corals offer to the coast and to fishes and invertebrates. I never would have expected to witness an ecosystem change so quickly, in just the first few years of my PhD. However, many organizations are hard at work in the Keys assessing the ongoing issues and coming up with plans to restore the reefs. It remains to be seen whether the restored and remaining species will be able to will be able to adapt and/or acclimatize to their new reality. If you want to see the reefs in the Florida Keys, I would suggest doing so as soon as possible, and to keep in mind the rapid pace of ecological change happening there.

Literature Cited

Rippe, J. P., Kriefall, N. G., Davies, S. W., & Castillo, K. D. (2019). Differential disease incidence and mortality of inner and outer reef corals of the upper Florida Keys in association with a white syndrome outbreak. Bulletin of Marine Science, 95(2), 305-316(12). https://doi.org/10.5343/bms.2018.0034